|

Photo cred. Ben Malcolmson

|

Intro from Chef Lily:

I have been studying peatlands for the past three years as part of my PhD in environmental history and so I spend my days thinking about the ways that humans and nature have interacted in these landscapes in the past, and how these interactions have led to the situation we’re in today. But beyond this work, bogs are such special and essential landscapes to me. They are sites of unbelievable beauty and life – nothing is more special than experiencing the vastness of a peatland stretching out before you. There is a kind of stillness and calm that you feel at first before all the complexity of the animal and plant life slowly creeps into your awareness. Seeing sphagnum moss in shades of green and red fills me with optimism and joy as this plant means the bog is alive and growing. When I spend a day at a bog, or talk to people about their connection to bogs, I feel a part of the long history of these spaces that began thousands of years ago and hopefully will continue for many more. |

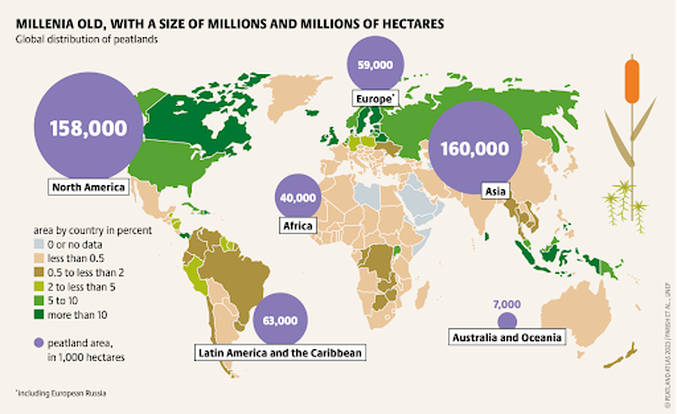

Peatlands, among which are bogs, fens, mores, and mires, are a type of wetland ecosystem that develop in areas where the soil remains consistently wet throughout the year, preventing dead plant matter from decomposing completely. This leads to the formation of giant mats of organic material that accumulate slowly over time - we’re talking only about 0.5 - 1mm per year! They’re found on every continent, in every climatic zone, and cover nearly 3% of the earth’s surface. Despite their relatively small proportion of surface area, these ecosystems provide an abundance of benefits not only to humans, but to the plant and animal species that call them home.

Despite their importance, peatlands often don’t get the recognition that they deserve. So, we’d like to share with you why peatlands are so important and what Trails & Roots is doing to help protect them!

This map shows how much peatland you can find on every continent. 90% of countries worldwide have peatlands!

Diverse Ecosystems

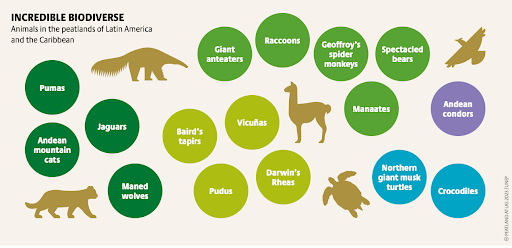

Peatlands support lots of diverse plant and animal species, many of whom are endangered, though the life that they support varies depending on the biome in which they are found. For example, peatlands in temperate regions, such as Ireland, are often marked by landscapes swathed in mossy, grassy vegetation with few trees that are home to waterfowl, otters, hares, and frogs. In warmer, tropical climates such as in Southeast Asia or Central Africa, peatlands are often covered with forests that support species such as forest elephants, lowland gorillas, and chimpanzees. When these diverse ecosystems are not degraded they are incredibly resilient and are better able to withstand natural disasters, support our water cycle and provide us the air we breathe, and they greatly help us in the fight against climate change.

Many of Latin America and the Caribbean’s most iconic animals call peatlands home.

Water Storage & Water Quality

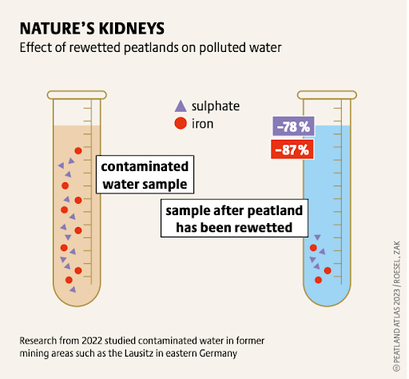

Not only do peatlands support incredible biodiversity, in some areas they also naturally filter the water. As water passes through the peat, pollutants get filtered out, making peatlands vital to the water quality downstream. They’re also significant sources of drinking water for many.

In Ireland, peatlands serve as the source of drinking water for a whopping 68% of the population!

It might seem counterintuitive, but peatlands also help prevent floods. They do so by capturing and storing enormous amounts of water, helping to prevent floods further downstream. By storing so much water, they are also able to help relieve drought in some areas. Unfortunately, climate change is making peatlands drier, making them more at risk for wildfires. These wildfires, as we know, release large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere - even more so when we consider how much carbon peatlands store.

Peatlands, even rewetted ones, filter an incredible amount of contaminants out of water! This image illustrates the result of research done in 2022 that showed a reduction of 87% of iron and 78% of sulphate from the water thanks to peat’s filtration.

Carbon Sinks

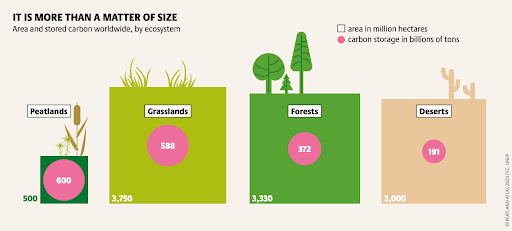

Globally, peatlands store about 30% of the world’s soil carbon - that’s twice as much carbon as all the world’s forests combined! Persisting for thousands or even tens of thousands of years, peatlands are a fantastic long-term carbon storage and are the most efficient carbon sinks on the planet. However, this means that when we destroy them, we can’t replenish them in a matter of years. When peatlands are dried out, they go from being carbon sinks that absorb and store carbon, keeping it from the atmosphere, to being sources of greenhouse gasses that are released into the atmosphere, exacerbating the greenhouse effect and worsening the climate crisis.

Today, about 15% of all peatlands have been dried out. That alone causes about 5% of all man-made greenhouse gas emissions.

This is a staggering number when you consider how little surface area peatlands occupy globally. The biggest threat facing peatlands are land use change (mainly for agriculture) and artificial drainage.

As we can see here, despite their much smaller area, peatlands store more carbon than any other type of land based ecosystem in the world!

What are Peatlands used for?

Historically, peatlands served a variety of functions to the people who lived around them. For centuries, dried out peat bricks were used primarily as a source of domestic fuel (known in Ireland as turf!). Today, peat is mainly used for potting soil. The main threat to peatlands, however, is modern day intensive agriculture which often has high fertilizer use. Peatlands are dried out and cleared to either grow crops which are then used as animal feed, or to raise animals for human consumption, particularly beef and dairy.

In the EU alone, ¼ of peatlands are used for agriculture!

In Borneo, Indonesia, the clearing of peatland rainforests for oil palm plantations threatens the survival of orangutans, whose habitat loss has made them critically endangered.

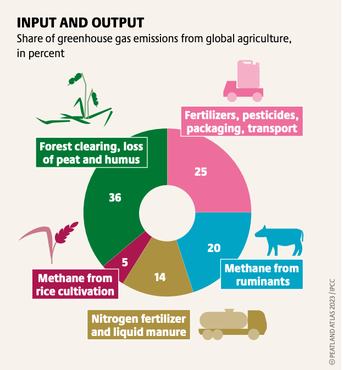

This chart shows us that within the agricultural sector, more greenhouse gasses are emitted from clearing forests and peatlands than from any other part of the system.

What can we do to protect and restore peatlands?

Strengthening regulations can facilitate the creation of regional and/or national parks and protected areas, protecting peatlands and preventing the further destruction of these precious ecosystems. It’s also important that governments remove subsidies (especially in the agricultural sector) that drive peatland degradation. Unfortunately, for the peatlands that have already been dried, much of the damage cannot be restored. However, there are ways to rewet peatlands to prevent further carbon dioxide from being emitted.

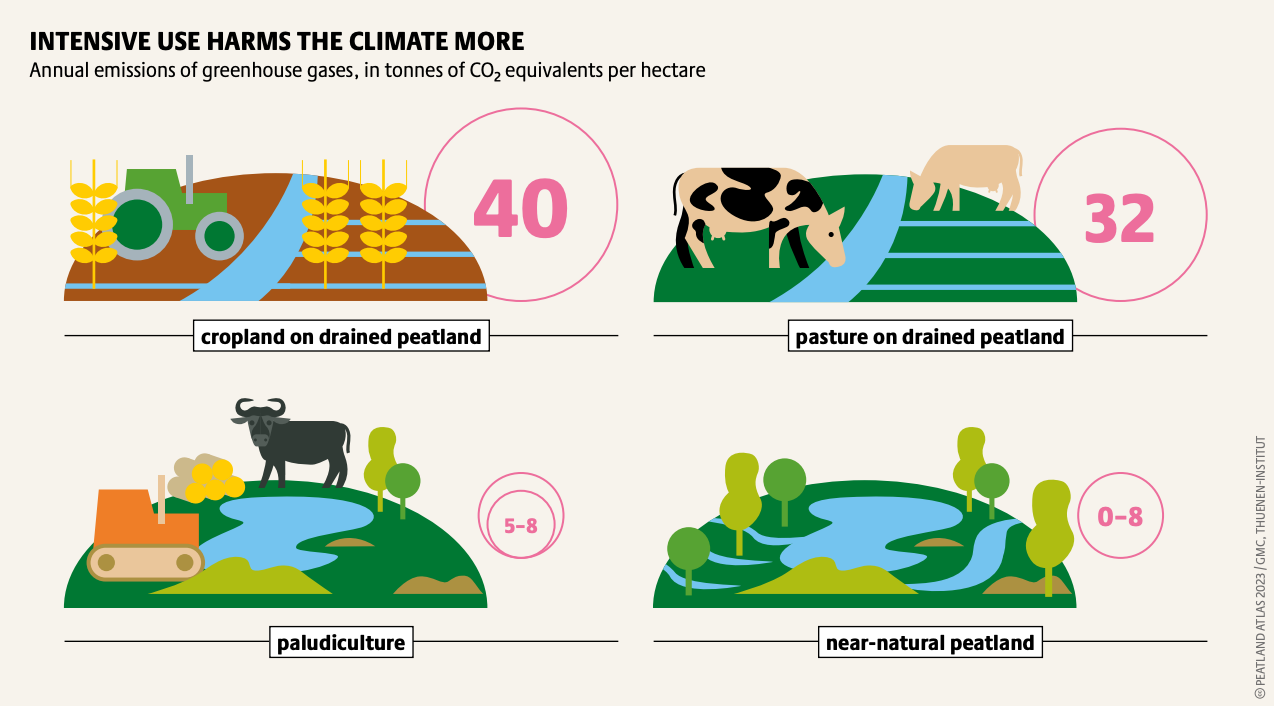

Keeping peatlands from drying out doesn’t necessarily mean that they cannot be used. A type of peatland-friendly agricultural production system called paludiculture uses species suited to the local environment and applies harvesting techniques that don’t destroy the soil. Paludiculture can achieve notably reduced (and even sometimes zero!) emissions, all while allowing us to farm sustainably on the peatlands.

Keeping peatlands from drying out doesn’t necessarily mean that they cannot be used. A type of peatland-friendly agricultural production system called paludiculture uses species suited to the local environment and applies harvesting techniques that don’t destroy the soil. Paludiculture can achieve notably reduced (and even sometimes zero!) emissions, all while allowing us to farm sustainably on the peatlands.

Comparing different types of agriculture, we see here that paludiculture emits up to eight times fewer greenhouse gasses than traditional agriculture.

But what can we do as individuals?

Important steps in the fight to protect peatlands include:

- Raising awareness of their importance

- Learning about and sharing the crucial role they play in the fight against climate change

- Adopting beneficial alternatives to their current destruction

It’s also why we here at Trails & Roots have chosen the Irish Peatland Conservation Council as the beneficiary of our 1% for the Planet donation!

1% for the Planet Donation to the Irish Peatland Conservation Council

|

The Irish Peatland Conservation Council is a nonprofit organization that works to conserve bogs in Ireland and protect the wildlife found within. Their work includes:

Additionally, they have:

Thanks in large part to the Irish Peatland Conservation Council, over 2500 square kilometers in Ireland have been designated for conservation by the Irish government! That’s the size of the entire country of Luxembourg! |

It’s estimated that for every €1 that is spent on nature restoration, between €4 - €38 is returned in ecological benefits!

Closing Note from Chef Lily

The science around peatlands is clear and there is a special opportunity to restore these incredible ecosystems to a level that means greater biodiversity and climate change mitigation.

So why can action often feel so slow and so difficult?

In the complex political and social systems in which we all live, competing ideas about the value of nature shapes how we interact with it. Groups with power are often the ones who get to decide what has value and how non-human environments should be used and exploited. Not only that, but the ways that communities are embedded in the landscapes in which they live further entrench ideas of ownership and survival. The history of peatlands in Ireland is an excellent example of the ways that action can be complicated, and also the ways that it can be possible.

A History of Irish Peatlands

|

For rural Irish people, peat has historically been the fuel of choice for heating and cooking food due to availability, accessibility, and cheapness. Trees were a rare commodity in Ireland and so communities developed intimate relationships with peatlands to extract fuel as a means of survival as early as the 5th century. The process of extracting peat was seasonal and required an understanding of water systems, peat composition and specific skills with tools that were developed over generations.

|

Ideas for the large-scale interventions into these landscapes emerged in the 16th century, with British landowners attempting drainage projects to convert peatlands to agricultural land. In what is known as the ‘Age of Improvement,’ imperial elites invested significant time and energy into surveying and mapping Ireland’s bogs in order to improve what they considered to be wastelands.

Following independence in the early 20th century, the Irish state began implementing policy interventions regarding how natural resources were framed in the context of energy security, industrialisation, and national development. This meant that while peatlands were being drained and extracted for fuel on a large scale, there was also investment in infrastructure and services for rural communities. These developments established strong links between workers and the land.

Following independence in the early 20th century, the Irish state began implementing policy interventions regarding how natural resources were framed in the context of energy security, industrialisation, and national development. This meant that while peatlands were being drained and extracted for fuel on a large scale, there was also investment in infrastructure and services for rural communities. These developments established strong links between workers and the land.

But besides being simply a means of either survival or rural and national development, peatlands and peat fuel have wider cultural meanings. In Gaelic Ireland, they represented significant spiritual spaces, portals to other realms, and privileged burial sites.

|

Chief Running Officer, Heather, trail running in The Slieve Bloom Mountains Nature Reserve - Ireland's largest state-owned Nature Reserve, ensuring the conservation of the mountain blanket bog ecosystem. Photo Cred: Conor Lucey

|

They would later come to be places of superstition and folklore and have a significant place in Irish literary culture. Attitudes and beliefs about the need to protect and restore peatland ecosystems were internationally recognised with the 1971 Ramsar Convention on Wetlands under the influence of diligent actors within the scientific community. In Ireland, these ideas were further embedded through local actions and the eventual adoption of the EU Habitats Directive in the 1990s.

Actors within communities which had been previously embedded in the peat industry are often to be found at the forefront of protection efforts. Ideas about the value of the environment exist within a context of power, access, necessity, and survival, and values are constantly changing. People have the means to impact the ways that we view the non-human world and take action from a place of justice and holistic understanding. Acts of restoration on the bog are a necessary part of the reparative phase of our entangled history.

|

Have a topic you want us to explore in our Rooting for Sustainability series?